Funny Hospital Patients Using the Call Light

It's hard to hear the phrase "hospital lighting" without shuddering. We're used to harsh overhead fluorescents which, while bright enough to allow doctors and physicians to treat their patients, grate on the retinas and obscure an innate sense of day or night.

That lighting style is also not especially conducive to advancing patient health and recovery. What might be is a system of adjustable LEDs that mimic natural daylight cycles, supporting patients' ability to rest, and creating a warmer, more comforting environment in their rooms.

In 2013, lighting megacompany Philips launched Hue, a wireless LED home lighting system that allows a user to control, via remote control, their lights, changing them to around 16 million different colors. With Hue, people can adjust the saturation and intensity of the lights to boost concentration or relaxation–Rensselaer Polytechnic University has conducted research on lighting's effect on humans–or just to create a certain mood.

In the home, "tunable" lighting is a nice luxury. But in institutional settings like hospitals, designers at Philips Lighting thought, it could be an asset. "Because of all we know about the science that has emerged, and how we have the power to positively impact people with lighting, it was an opportunity we couldn't ignore," Patricia Rizzo, Philips Lighting's senior lighting applications designer, tells Fast Company.

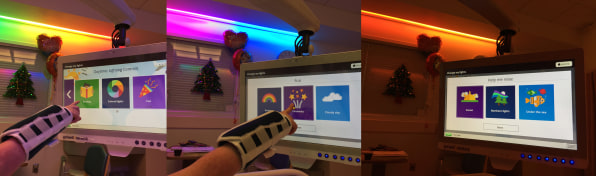

Last year, Philips Lighting partnered with the University of Minnesota Masonic Children's Hospital to install a pilot of adjustable LED lighting systems in a handful of patient rooms in the hospital's pediatric intensive care unit. Around 10 lights–situated not just directly overhead, as is standard, but at various points along the ceiling and walls–comprise the system, which both hospital staff and patients can control via an intuitive, tablet-like interface. The lights automatically adjust in accordance with the time of day, and the number of occupants in the room, but manual controls–say, if a doctor has to check up on a patient in the middle of the night–can override standard settings.

The dynamic new system, Rizzo says, accomplishes a number of things: "One, it's not a static environment, so the patient has some sense of the time of day," she says. Especially in ICUs, delirium affects up to 80% of patients; those impacted tend to have longer hospital stays and a lower six-month survival rate than those without it. While the pilot program is too new for UMMCH and Philips Lighting to have been able to fully analyze the data, they believe that the adjustable lights will allow their patients to sleep more soundly and avoid delirium.

In creating the system, Philips Lighting was looking to strike a balance between providing caregivers and doctors the necessary conditions to carry out their work, and granting patients a certain measure of control over their environment. Unlike the more standard white lights overhead, the lights on the walls on either side of the bed, Rizzo says, emit different colors, which patients can adjust at will. "You might get a series of chasing colors–from blue to pink to green–that's just a positive distraction for the children," Rizzo says. At night, patients can also, via the tablet control system, choose to play music along with the change in lighting.

"It's a really emotional experience to be in those rooms, versus those lit with standard lighting," Rizzo says.

In addition to the patient benefits, the lighting systems reduce per-room energy consumption by as much as 80% and could allow hospitals to reinvest the eventual cost-savings toward other improvements. By next year, Rizzo says, Philips Lighting hopes to see the lighting systems scale up to more rooms in UMMCH and other medical facilities. And coming up next: Philips Lighting wants to apply this same tunable lighting technology to office buildings.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/40502528/replacing-awful-hospital-lighting-could-create-a-more-healing-environment

0 Response to "Funny Hospital Patients Using the Call Light"

Post a Comment